Sunlit Smoke

by Annie Lindenberg

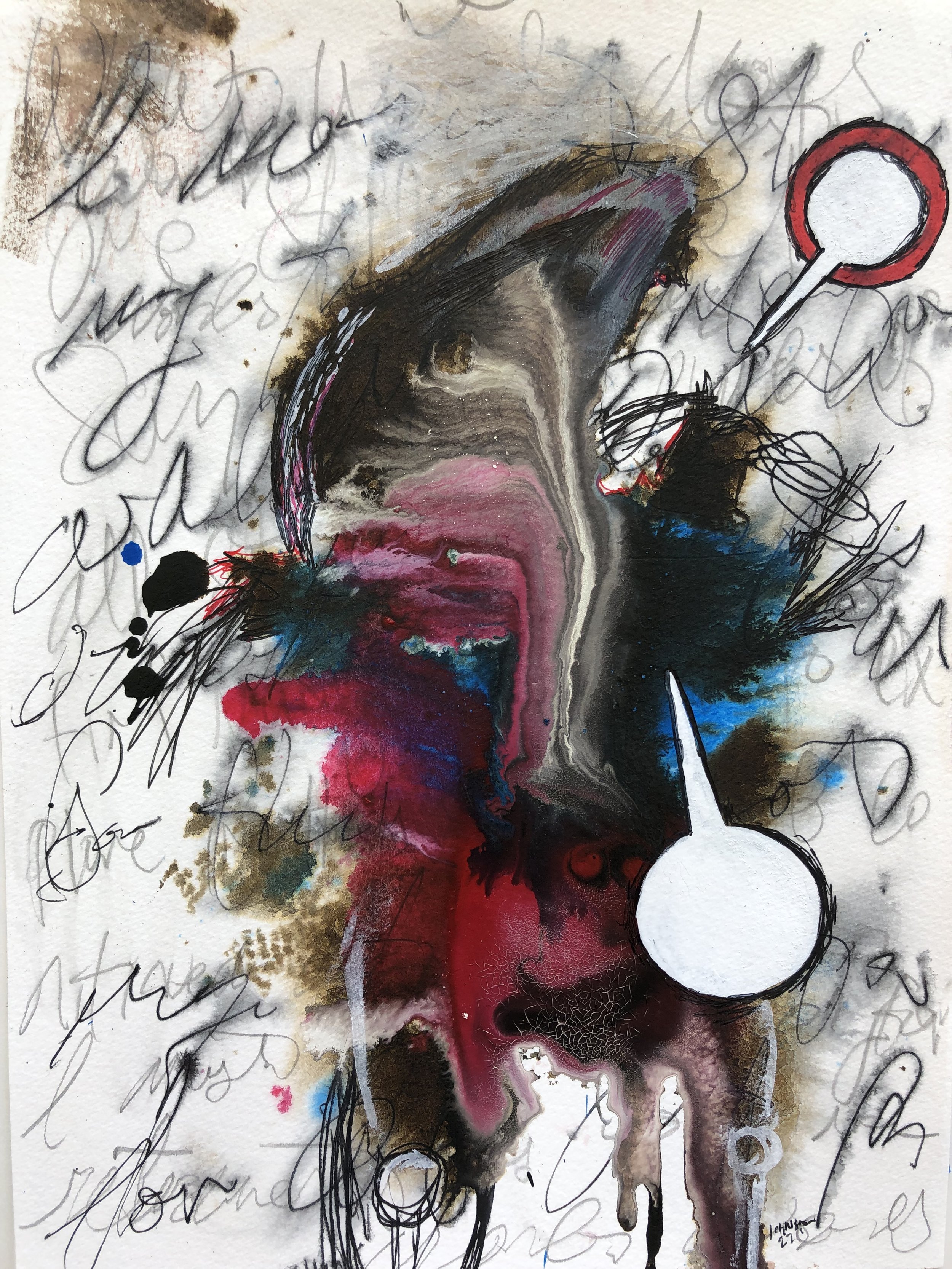

Featured art: “Public Address 3: Phantom Limb Mandrill” by Jeff Johnston

I exited out the back. My feet took a few steps from the building—one, two, three—before they turned me around the corner of the rusting black dumpster to come to a halt. All the heat of the sun seemed to be pulled directly to this place, and Ms. Jamieson stood on the other end of it—sweating and smoking a cigarette. Fitch’s mom.

The cigarette between her fingers glowed inches from her face as she stared at the parking lot. Fitch was always complaining about people calling her hot. It probably stung because it was true. She held effortlessly to her youth; hell, she was still young. Yet, as she stood there in a black dress that was thoroughly wrinkled down the front, she looked aged beyond her years. Still she was gorgeous, effervescent somehow—all thick, burgundy hair and full lashes. Like she’d stepped straight out of the ‘70s as a poster child of the free love movement.

“Ainsley.” Her voice was thin, but edged with the beginnings of a gravel. She sounded tired, but otherwise she sounded the way she always did. Coming home from her shift, finding me and Fitch on the couch binging reality television as we half-heartedly did homework, standing briefly in the doorway before wandering away.

“Caught me,” she said, holding up the cigarette. She rolled it between her fingers and looked close to throwing it to the floor. She brought it to her lips instead. “Want one?”

“Oh, uh– no, I–” My hands ran down my chiffon blouse, doing nothing to halt the sweat pouring from my palms. “Fuck it. Yeah, if you have one.”

She pulled a near fresh pack from her purse and held it out to me with a lime green BIC lighter that was hilariously out of place. I took a cigarette and grasped the lighter between slick fingers. My hands weren’t steadying, but after a few clicks I was able to light it and pull in a heavy smoke-filled breath. It settled me instantly—evening me out. Like the smoke had bellowed through my body until it found all my holes and kindly filled them.

“You’re in Chicago, right? Northwestern?”

I nodded. She shouldn’t have asked me that. It was like asking someone in the emergency room if they’d left a lamp on at home. Unbelievably arbitrary.

“That’s good. A good school.”

Her voice was flatter than usual, and I wondered if it was because she was tired or because we were here. Maybe now that Fitch was dead the civility she had long held onto for me as his best friend had flattened, too. What did I matter to her without him? Looking at me was looking at a cropped photo and wondering where the other half had gone and why.

“Yeah, it’s been good.” I winced. My palms felt sweatier still. The cigarette seemed to dip where the moisture dampened it. Silence slithered between us. I wondered who it would bite first, poisoning with discomfort and the things that could be said but stayed firmly locked in both of our mouths. “Ms. Jamieson–”

“Ainsley.” She fixed me with a look. “Just smoke your cigarette.”

“Yeah.” I leaned my back against the dumpster, and the heat singed my shoulder blades. It was painful but not unwelcome. I took a drag and the smoke burned; with no more holes to fill, it found its way to my brain and left me dizzy.

“Were you leaving just now?” she asked.

The truth didn’t seem hard beside her. “I’m not sure, but I don’t think so.”

I searched for signs that it bothered her, but there was no motion in her features. How did you do makeup for your son’s funeral? I could picture her sitting at the worn vanity in her bedroom—the one she’d found at Goodwill when we went there looking for new school clothes for Fitch—and laying on a delicate layer of blush. The way she would lean forward with weary eyes and swipe the mascara on. There were a number of nights Fitch and I had snuck into her room to do the exact same thing.

The memory of Fitch leaning his head backward as he sat at her vanity, blonde wavy hair long enough to graze his bony shoulders falling away to reveal the sharp lines of his face, played on the inside of my eyelids like a well-worn record. He was beautiful in the way a statue was beautiful. All you wanted to do was look at him, and yet there was something impossible to understand, a mystery underneath those marble features. He looked nothing like his mother.

Every night I returned home from theirs, which was most nights, I would fall asleep thinking about those two in their shoebox of a house. I would fixate on the image of both passing by each other like the two lone cars on the highway late at night. Why are you still up? Where are you going in such a hurry? Who are you?

We never did his makeup flamboyantly. He always wanted to look crisper, cleaner. I’d line his eyes and color his lashes. I made his brows sharp and contoured his fine jaw and cheekbones. By the time we were done I could have sworn he had walked right from a magazine cover. That perhaps he would turn around and ask me what I was still doing there, like I’d been merely dreaming.

“I left my mother’s funeral,” she said.

I snapped out of the memory, and it left my chest hollow. What if I never remember this one again? It was a constant worry that still plagues me. What if this is the last time I will touch this imprint of our lives? Memories too slippery to hold. I stopped my self-pity, eyeing her—I don’t think she was wearing any makeup at all. Or if she had she’d already cried it off, but I ignored that idea.

“Yeah?” I prompted. My cigarette had died off in my fingers without me realizing. As if sensing it, she held the pack out, and I grabbed another. I didn’t need it, but I needed something to do, something to prolong this moment.

“I was meant to give a speech at her funeral, but I hadn’t planned a thing. Every time I tried to think about what to say, it was like there was this blank page in front of me with no way to fill it.” She shrugged. “I just left. Probably better for everyone that way.”

My own mother was standing inside eating appetizers while she chatted in low tones with other moms. I could imagine the conversation perfectly. Slipping in and out of tragedy the way you could do only when it wasn’t yours.

During the sermon, my mother reached to touch my arm. I assumed it was an act of reassurance, but knowing that didn’t stop me from flinching. The idea of being touched by someone who didn’t understand my body’s newfound starvation disgusted me. Loss wasn’t heavy for me; it was the opposite. My body felt lighter, barely touching the ground, and I worried if I allowed her touch she’d somehow pull my feet back to the earth with apathy.

“What did your dad say?” I asked.

She shook her head. I suddenly couldn’t remember what her first name was. I had grown accustomed to thinking of her as Ms. Jamieson. Margaret? Madeline? It was definitely something with an M. I tried to imagine Fitch forming the name with his pink-lipped mouth, but all that appeared in my memory was a hollow image like a muted television screen.

“He didn’t say anything. I lived on my own at that point, so I didn’t talk to him until maybe a month later? He didn’t acknowledge it.” She paused. “We never did.”

The wind rustled past, sending the smell of smoke wafting through my hair. It hovered just below my chin, and it was fine enough to flutter every which way with just a breath of air. I tucked it behind my ears the best I could. I thought of Fitch in the casket with his waving blonde hair that would forever be longer than mine. Golden still after everything else had disintegrated.

I looked at her again. Madge. Ms. Jamieson went by Madge. Fitch had told me that, and the muted television screen found its sound in my memory. Learning her name brought a clarity I could feel in my chest. It was like seeing a painting’s title for the first time. Oh, so that's who you are. That's who you’ve always been.

The cigarette was tucked between her lips as she used both hands to pull her hair back, but there was too much of it. The strands flew from her palms before she could tie it up. The cigarette burned with a sudden inhale, then dipped at a wayward angle her lips couldn’t fix alone, and she dropped the hair to pull it from her lips.

There was no logical explanation for what took over me. I dropped the last of my cigarette to the ground without bothering to stamp it out. “Here,” I said.

Then I walked over and took her hair between my hands. It was silkier than it looked. She was a few inches taller than me, so I reached up to feather the hair away from her face. My fingers smoothed over the flyaways before tucking back the little hairs by her ears. I gathered it at her nape delicately, intimately. For a second I stood in stillness—the tail of hair firmly in my grip. Then she offered me the ponytail she had around her wrist, and I tied it back.

I didn’t want to step away or let go of my hold on her. There wasn’t a thing that could make me want to leave that moment and the idea that if I touched her skin it would all make sense. The audacity of me to have thought I understood her loss, but even now I still think there’s some part of me that does more than anyone else.

Fitch was my world, and death never changed that. I fall asleep, and I see his round green eyes staring back at me, and all I can do is reach out for a hand that is no longer there. I wake up and think what was he telling me to do this time? At times I wake up and expect him to be on the other side of my mattress, as if his death was the real dream.

“Thanks, Ainsley.”

I couldn’t stand there any longer. I knew I needed to step away, but I wanted to crawl underneath her skin and burrow in her stomach. The idea of being curled in her abdomen was a particular delight. In a feral way I couldn’t explain, I wanted her to love me. I took a step back and begrudgingly gave up my hold on her. She turned to look, and her eyes were his eyes. Fitch’s eyes had been hers, more aptly. Green and wide. They looked like they belonged in another life, on another face—unnatural but beguiling.

Ms. Jamieson’s hand came up and tugged at a lock of my hair. As quickly as it came it fell. “Fitch loved you.”

She didn’t say it reassuringly. It was like an afterthought, something to say to fill up the space that was too empty around us. Perhaps it was empty because we knew exactly what should, and couldn’t, fill it.

I wanted to ask what she was going to do now. The idea of that house, of her alone with only the ghosts of who used to help fill it, rattled me. A boyfriend who couldn’t stay to be a father and ran away. A son that took one wrong pill and never woke up. Now there was only one. She had restarted her life before she hit forty, and all she probably wanted to do was go back. Would she do it all again if she could? Or would she choose something different so she wouldn’t end up here, smoking a cigarette next to a dumpster with a girl half her age who wanted her to explain the world in a way that would make sense.

Fitch loved you. I should tell her how many calls of his I sent to voicemail in the last few weeks of his life. Or maybe about the time he’d come to stay in the dorm with me and how drunk he’d gotten, barely able to stand on his feet. It had seemed funny in the moment, but funny because calling it anything else would have felt like a betrayal. When we’d stepped out of the party to turn home, he hadn’t seen the stairs. He stepped forward like a cartoon character over a cliff, expecting there to be land to hold him and hovering for an impossible moment, but he fell down the six front steps bonelessly.

I reached out my elbow to scoop him up (he had laughed immediately—a sunshine laugh that I knew only to be true then), and we leaned into each other the whole way home. We whispered secrets and nonsense and the truest things we’d ever say the way all drunk people do. He fell into my twin size dorm bed before I did, and when I finally slipped under the comforter and curled toward him, he smiled at me.

“I love you, Ainsley Jones.”

“I love you,” I answered. It was the truth, and there was nothing else to say. His eyes fell shut within a minute, and as his breathing evened out I felt a soundless sob crack in my chest. There was a cut above his eyebrow I hadn’t noticed. It looked like the silhouette of a bird, the three drops of blood already dry on his forehead below the wings.

My hand hovered over the mark as if by its own volition. The moment no longer felt real, but as if I was looking at the two of us in a funhouse mirror. Me—now taller than him; him—squat and short.

“I loved him,” I answered. My voice was thick. I knew then that no one would ever be able to talk to me about Fitch for the rest of my life the way Ms. Jamieson could. Talking to anyone else would be unsatisfying, but it would also feel fake. Exploitive.

She eyed me. Her lips curved up minutely, almost imperceptibly. I wasn’t sure if I was imagining it. “Here.” She offered me the cigarette pack in her manicured hand.

“I really don’t need them,” I said with a small laugh.

Her lips soured. I realized she didn’t know what else she could give me, but she wanted to give me something. What did a half-finished box of cigarettes mean, though? Every smoky aftertaste from them would leave my brain clouded with visions of her. “Thanks.”

“You can stay or you can leave, Ainsley,” Ms. Jaimeson said. She passed me and stepped toward the door, hand on the knob, as she turned over her shoulder to look at me. “It won’t mean a fucking thing to him.”

“What about to you?” I asked. It came out like a reflex.

The question surprised her. A blush took over her cheeks, and her hand fell from the door as she took the three steps back toward me. The same hand that a few minutes ago had tugged on a lock of my hair now reached up to my face. Her thumb brushed the edge of my mouth, and then it met the other fingers and cupped my cheek. I’m still not sure if she was seeing me or someone else.

“Come see me sometime when you’re home.” She shrugged. “Or not, Ainsley. It’s your life.”

Even now when I think about Ms. Jamieson, I have the same image of her. She’s sitting on the recliner in her living room with a straight back. Her hands are cupped in her lap as if she’s waiting for me to return. Maybe she’s waiting for everyone to return—all the people that left and never came back. I hadn’t once seen her sit there or anywhere in that house, actually. I’d only sat with her once on the night when she’d taken us out for dinner after our graduation.

Fitch and I were squeezed together on one side of the booth as we still wore our caps and gowns. On the other side of the sticky tabletop was Ms. Jamieson as she watched us with amusement. It felt like we were two animals on exhibit at the zoo, and she was tracing our movements. Perhaps she knew what I hadn’t then—that memories were fragile, and they needed to be stored.

“You’ll do good things,” she said to us. Then she snorted and shook her head. “Or not. I’ll be proud either way.”

Fitch rolled his eyes. “Real motivational, mom.”

She shrugged. “Love isn’t conditional. Drink your damn milkshake, kiddo.”

Fitch hated being called kiddo, but I remember he smiled. A light one. Maybe he was happy being kiddo for just a minute longer. Maybe I’ve molded the memory to fit my own agenda, my own narrative. But what does it matter to a dead boy I will never get back?

“Yeah,” I said now. Ms. Jamieson’s hand dropped at the sound of my voice. Maybe it broke the trance, and it was me in front of her again. “I’ll have to come see you.”

This time when she turned she did not turn back, and she disappeared into the building. I stared at the door that had cracked paint and a rusted handle. I turned and eyed the parking lot scattered with cars. Still unsure, I tipped my shoulder blades back against the scalding metal and pulled another cigarette from the pack.

Annie Lindenberg is a MFA candidate in Fiction at Minnesota State University, Mankato, where she also works as the Graduate Assistant for the Good Thunder Reading Series and as the Head Fiction Editor for Blue Earth Review. Her work has previously been published in The Tower Journal and forthcoming in Cutleaf Journal.

Jeff B. Johnston was born, raised, in Tulsa, Oklahoma. He earned a BFA from the University of Tulsa, Oklahoma, where his love of fine art began. A graphic design career took Jeff in 2003 to Baltimore and Washington DC, where he exhibited in a number of gallery spaces. Jeff's design career led him to Los Angeles in 2009, and in 2012, to San Francisco. He earned his MFA in studio art at the San Francisco Art Institute (2016), and continued to be involved with SFAI until its recent closure. You can find his work on Instagram @jeffbjohnston.